Documenting artwork is tricky. I hire a local professional photographer to capture my large scale paintings, but most of my work is small enough to document using an A4 scanner. In this post I use an Epson V37 to scan a 20 x 24 inch piece of canvas in 8 sections, then stitch them together using Microsoft’s free Image Composite Editor.

I align one corner of the work in a corner of the scanner, place a light weight book on top of it to keep it flat, cover it all with a piece of dark fabric (I use black felt but anything that blocks the light will do), and take a preview scan.

In professional mode, I set the document type to reflective, the exposure type to photo, the image type to 24-bit color, and the resolution to 600 dpi (300 is probably more than enough, and any higher than 600 will make ridiculously huge and heavy files).

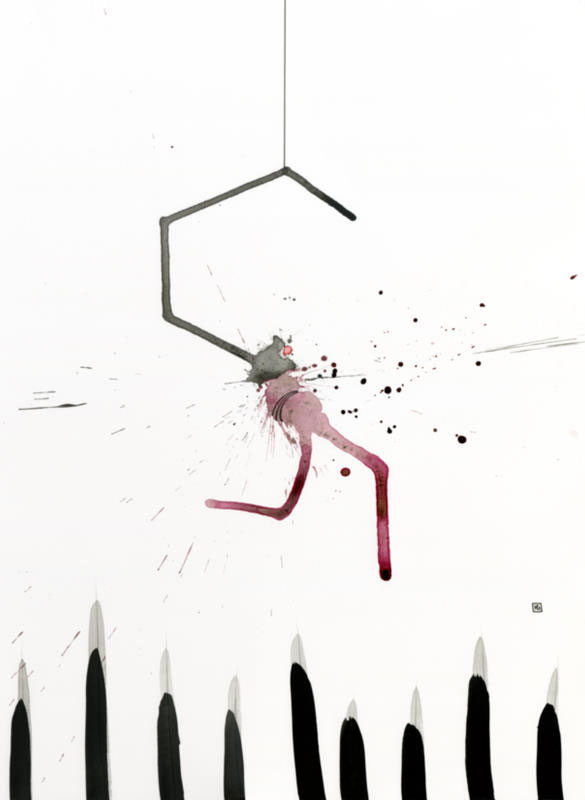

For scan section #1, I’ve aligned the scan window (the dotted rectangle) with the corner of the work. The scan window will need to be realigned every time I change from a corner to a middle scan, a middle to a corner scan, or a corner to a corner scan.

In this case, I’ve set the document size to 8 x 11-1/2 inches, which is marginally smaller than the scanner bed size and gives me 1-1/2 inches of overlap on my rows. It’s better to make the scan window smaller if you can, because the light changes as the work lifts off the scanner bed where it overlaps, leaving a shadow in the scan (which is more noticeable on white paper than raw canvas).

The first time I press Scan, I choose a destination folder for my scan sections by selecting Other and then Browse… All subsequent scans will go to this folder, and the system will automatically number them as I continue.

I click OK to scan the work, then move it across to scan the next section. The canvas is 24 inches wide, so I will scan each row in 4 sections of 8 inches each. The stitching software performs best when the sections are evenly distributed across the work, so I try to move it the same distance for each new scan. The face of the artwork is actually touching the scanner glass at this point, so I am extremely careful while manipulating it’s position. I also remember to use the book and the black felt for each scan section.

After scanning my two middle sections, I move the scan window to align with the corner of the work.

Now I move the work (and the scan window) vertically, to start a new row of 4 sections.

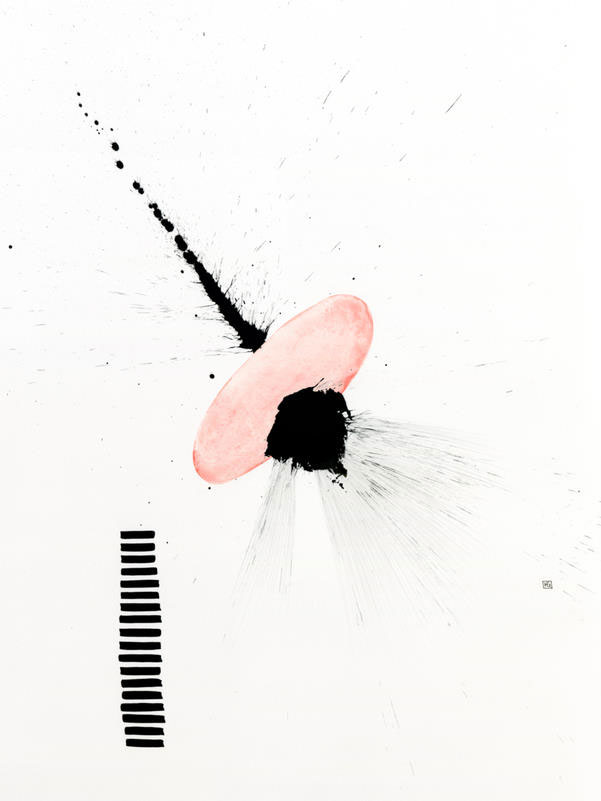

Now it’s time to open the ICE software, and select New Panorama from images. I navigate to the folder with my scans and select all the sections for this work.

I select Structured panorama and set the camera motion to Planar motion. Then I click on the initial corner and direction to set up the layout. If it doesn’t align, I check to make sure that I have the right number of columns, and either Serpentine or Zigzag selected for the image order, depending on how I took the scans. In this post I used Serpentine order, meaning that I went in one direction for the first row and then back the other direction for the second row. I select Auto overlap then go to the top and click Stitch.

After I’ve fixed the orientation, I click Crop.

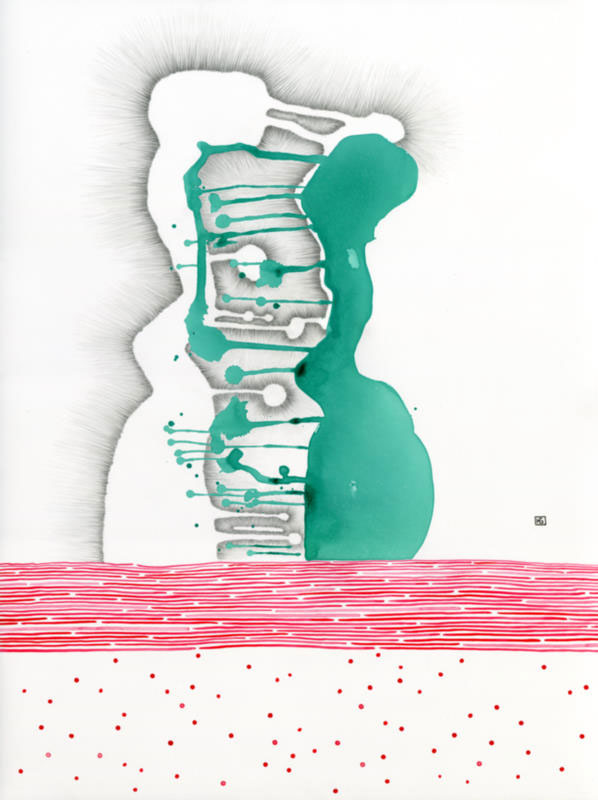

After I’ve cropped the work, I click Export, and save a copy of the file as a full sized tiff, a medium jpeg, and a small web jpeg. Re-exporting the file at different sizes now is far quicker than re-opening it later. Most artist submissions require a file that is close to the medium jpeg, and while it’s important to have the larger tiffs for printing, it’s good to have a light weight image file that is quick to open and work with, as well as small copies for email/internet uses .

When I close Image Composite Editor, I discard the project because I’ve already saved the tiff and jpeg files. I also go into the scan section folder and permanently delete the section scans to save space on my hard-drive. I keep several copies of all the full sized tiffs in several places because once these works are sold this is all I have left of them (and we all know that computers sometimes go to computer heaven at inconvenient times).

This scan and stitch method is fairly straightforward as long as one side of the artwork is no larger than 20 inches, so it can be scanned in two rows, both of which align with an edge of the scanner to keep the work level. I have used this method with larger works on paper, which required three rows of scans, but it was very difficult to keep the alignment on the center row. That said, it can be done if you are extremely patient, meticulous, and willing to create a raised jig-like structure around your scanner with guidelines to keep the work level as you move the middle row, and also to support the part of the work not directly on the scanner bed. If I ever perfect this technique I will make a post about it.